Wake Up, Dead Man (Everyone's Included Until Somebody Gets Stabbed)

When a powerful church leader is found dead, Benoit Blanc enters a tight-knit community where everyone has secrets, but not everyone is fully developed.

Blues music began by Black folks in the Mississippi Delta. And, depending on who you ask, it was either born from jazz, slavery, or while waiting on a train. It was shaped by the weight of the fields and the shadow of Jim Crow. In its sound went work songs, spirituals, hollers, and the silent grief. In the world of the blues, music was a sanctuary and something to lean on when the law, land, and times delivered less than little comfort.

From this environment emerged the legend of the “Crossroads.” Most of us know the tale famously tied to Robert Johnson about talent paid for with a heavy price. Whether these narratives are taken literally or not, the common theme they express is the reality that created the blues: Nothing comes without sacrifice. When films go to “crossroads,” they try to tell the history of the blues through the ideas and experiences of the people who created it.

Sinners takes that history and grounds its story in the lived experiences, fears, and hopes of the Black communities that shaped the Delta region. The 1986 film Crossroads, by stark contrast, tries to draw from those same traditions, but it ultimately treats its historic culture simply as folklore.

The blues in Crossroads is just a setting for another story that focuses on the “Karate Kid” Ralph Macchio at the height of his career. And it strays far from the culture that created the music. The two together reveal something about how film can either honor a legacy with clarity or turn it into something that’s easier, safer, and a lot less closely associated with the people responsible for bringing the blues into the world.

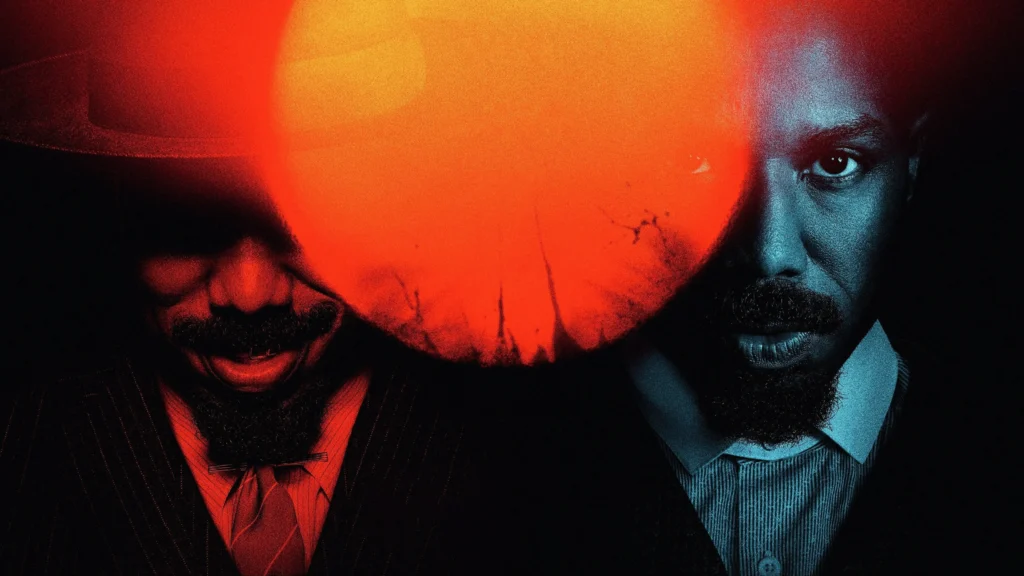

In the 2025 film Sinners, twin brothers Smoke and Stack return to their hometown of Clarksdale, Mississippi, carrying stolen Chicago money. The twins open a small juke joint in the famous Delta town where Robert Johnson sold his soul at the crossroads and Abe Davis sold his famous barbecue just across the street. Michael B. Jordan plays both brothers masterfully, giving each twin his own voice while navigating through the same, shared experience. You can check out our review and score of Sinners here.

Character Sammie Moore is the younger cousin of the brothers who enlist him to perform at their new joint. He is torn between his preacher father’s disapproval of blues music and the pull the guitar holds over him. He is portrayed by actor musician Miles Caton. And, in the film’s flash-forward to the early 1990s, Sammie’s older self is portrayed refreshingly by Buddy Guy, the only blues legend still alive today. And the dual casting shows a full arc from a conflicted boy in the Delta to a seasoned bluesman shaped by everything he survived.

The vampires in Sinners symbolize a deeper threat than fangs or hunger. They represent the long history of outsiders taking from Black life while demanding obedience in return. These former Irish balladeers and Klansmen move through Clarksdale with forced politeness. They offer “opportunity” only if the brothers surrender their sound and their identity. Their hunger mirrors cultural appropriation itself.

They desire to consume the music, labor, and spirit of a community without carrying any of its burdens (see 1991’s The Commitments). As the vampires push for assimilation, the film exposes how Black culture is too often stripped of context and sold back without its people. Smoke, Stack, and Sammie fight to defend the Delta blues from becoming another stolen inheritance. Crossroads attempts the same cultural theft, sucking the blood from the music and identity of the Delta for itself while tossing the people and their history aside.

Released in 1986, Crossroads follows a young classical guitarist named Eugene Martone, fascinated by the legend of Robert Johnson. Martone, played by Ralph Macchio, soon teams with an aging bluesman to search for a “lost” Johnson song in Mississippi. Macchio was fresh off the massive success of The Karate Kid, a film built on appropriating Japanese culture and presenting it as a path for a white hero’s growth. Crossroads repeats that formula, using Black music instead of Okinawan martial arts and treating both cultures as tools for a white character’s development.

In the film, Macchio’s character meets a fictional version of Delta blues singer Willie Brown, played by Joe Seneca, who becomes the soft-spoken guide for the boy’s “blues education.” Brown’s only narrative function is servile as he instructs, supports, and uplifts the white protagonist on a journey that has nothing to do with Black life in the Delta. The film strips him of his own agency to serve Macchio’s story. This dynamic mirrors the long pattern of Black characters being used as supporting furniture in stories that depend on their culture but ignore their humanity.

The film’s most infamous moment is, hands down, the climactic “showdown” guitar battle. Macchio’s character faces off against the Devil’s guitarist, played by shred virtuoso Steve Vai. The contest turns the Delta blues into a flashy and uncomfortable rock duel for ownership of Willie’s soul. Optics aside, the face-off is more “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” than anything blues. Originally written by Charlie Daniels, that song itself is just another whitewashed re-telling of older Black blues and folk tales about bargaining at the crossroads.

It seems, in Crossroads, the idea suggests that heavy metal is the next “evolution” of the blues, a claim that ignores the truth that metal and blues grew from entirely different cultural roots and experiences. The scene rewrites the blues into a spectacle where whiteness triumphs through speed and theatrics, while the culture that birthed the music is pushed aside. Crossroads becomes a caricature of blues history, flattening the tradition into a collectible skill set for outsiders while erasing the people who carried it.

Sitting side by side, the films pose a central question: Who gets to represent a cultural tradition? Sinners centers its story around Black people, both visually and narratively, who anchor their decisions and fears in what was reality at the time. Their music and their memories flow from the community and are shaped by its wounds and its resilience. Crossroads, by contrast, treats Black culture as the backdrop, which lets the white protagonist “inherit” the blues without regard to the circumstances that necessitated the music. It treats the Delta as a playground for white discovery and the blues (along with Willie’s freedom) as an object to win in a contest.

The actual horror in Sinners derives not from the monsters but from systems that haunted Black communities long before folklore made fear look alive. Racism, poverty, and silence are the film’s true villains. The blues grew out of those same shadows which Crossroads avoids altogether.

Related lists created by the same author

When a powerful church leader is found dead, Benoit Blanc enters a tight-knit community where everyone has secrets, but not everyone is fully developed.

Related Movie / TV / List / Topic

Based on the fairy character from previous movies, this fantasy movie gives viewers magic.