Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse Tells Us to be Our Own Heroes.

Miles Morales learns to be his own hero as he takes on the well loved mantle of Spider-Man in a multiverse of Spider-People.

Incluvie – Better diversity in movies.

Identity in film through scores, reviews, and insights.

Incluvie – Better diversity in movies.

Explore identity in film through scores, reviews, and insights.

It doesn’t make sense to assume viewers will mimic what they see on a screen, no matter how impressionable they may be. But that’s not the only way violence on screen impacts audiences. From causing distress to desensitization, insensitive depictions of harsh realities and violence have a myriad of negative effects. As Lisa Damour surmises, just as with suicide or smoking, sexual assault should be of importance in the conversation on what’s considered safe for consumption by teenagers and adolescents. I’d like to go one step further and suggest that maybe sexual assault can be addressed in cinema without ever portraying it on screen at all. From a point of view of necessity in the depiction of post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of rape or in those close to the victim, the rape scene barely contributes to the exposition. If anything, a poorly shot or distastefully made rape or sexual assault scene could just perpetuate harmful stigmas about openly addressing it, and even trigger viewers. So, at the center of this conversation lies the question “Who does a rape scene really serve?”

Now, I’m aware that dialogue isn’t always the best way of addressing something cinematically. I belong to the school of thought that prefers show over tell. But showing has its own limitations as it might, if not done with the utmost care, become an unwitting participant in what it attempts to critique. A great example of this is the film Blonde. It’s entirely possible that the creative team didn’t have the right intentions, to begin with, but I’m choosing not to be that cynical today. Whatever the intentions though, the film’s portrayals of Marilyn’s abuse and the innumerable transgressions against her are so unsympathetic that it seems complicit in the reduction of the woman into a commodity for speculation and worse, scopophilia. She’s inexplicably topless in a lot of scenes, and her abuse is filmed in such a way, it’s titillating and almost pornographic. So, it contributes to her abuse in a way.

When it comes to cult classics, the horror genre has always had an overwhelming number of B-movies. Horror B-movies refer to the low-budget feature films as compared to major feature films. One might call them “low-grade” cinema as opposed to the more artistic endeavours, but I’d refrain from saying that. The horror B-movie is a source of unbridled entertainment and for the fans of spooky business, it’s the perfect way to round out Halloween night or any night in which they’re in the mood for horror. Usually characterized by a somewhat loose storyline, sometimes some quite silly characters, a little over-the-top acting and a bunch of practical effects, horror B-movies used to rule the world of horror during the ’70s and ’80s with franchises like Friday the 13, Slumber Party Massacre and Halloween.

But since the late '90s, with big-budget horror films like End of Days and Hollow Man, the focus has shifted from the horror B-movie. We now have major horror features like It and Midsommar and every year, there are almost ceremonial releases from the studio A24 which gave us The Witch and Hereditary. This year itself, Ti West's X and Jordan Peele’s Nope came out, which are far from being horror B-movies. But that being said, it’s only the focus that has shifted because we still have horror B-movies being made. If you enjoy the bizarre, less refined and entertaining world of the horror B-movies and want a break from the nuanced and poignant big-budget horror releases, I have a list of gore-fests from the last ten years to enjoy this October. Here are fifteen films for the fifteen days that remain till the auspicious date of Halloween!

The biggest subcategory of horror B-movies by percentage is the slasher film. Almost overdone violence and heavy reliance on practical effects as opposed to CGI characterize the slasher. And of course, the heavily criticized but also equally loved trope of the final girl is a slasher staple. Some of the most gruesome on-screen deaths have been courtesy of the slasher horror B-movie and I’m here to offer you some more horrible killings. If gore makes you queasy, you may consider skipping this segment.

TW: Transphobia, Sexual Assualt, Violence, Misogyny // Spoilers for Sleepaway Camp ahead

We [meaning mainly the girls, the gays, and the theys] all love a good revenge film — Jennifer’s Body, Ms. 45, Carrie, and the new addition to the canon: Promising Young Woman. All the films feature a woman who enacts her own version of justice against those who are not being punished for a heinous crime — normally upholders of oppression like sexual assaulters. Though violent, sometimes exploitative, and not usually having a happy ending for the femme protagonists, at the center of these stories are questions about how justice truly functions in our society. As we’ve seen post #metoo, industries have slowed in making progress and even the so-called damaging “cancel culture” has not removed most abusers from their platforms. In this subgenre, fantasy and catharsis intertwine as one where we can escape to an alternate reality where the oppressed play karma in making those who killed our soul suffer in response. Though it does not fix the structural roots and usually punishes the women in the finale, the everlasting images are an escapist fantasy where related audience can feel sublime satisfaction that only comes with pure vengeance. That’s why we [see previous] love them.

For anyone who is not a cis white woman, a justice-fueled murderous rampage is not framed as liberation. Instead, they contribute to harsh stereotypes that vilify minority women with dangerous consequences. Particularly, trans women have been coded as serial killers for decades — especially since, possibly the most famous horror film ever, Psycho. The trope has expanded since then where explicitly or implicitly coded trans serial killers have made up some of the most well-known villains in horror and cinema history: including Leatherface, Bobbi, and, worst of all, Buffalo Bill. The most explicit — and “coincidentally” the most egregious, in my opinion — is the 1983 B-movie Sleepaway Camp. The protagonist is revealed to be trans, forced into being a girl by the eccentric aunt she is sent to live with after a freak boating accident kills both her sister and father. She goes on a killing rampage murdering all the bullies who torment and do her wrong during her time there. When Carrie did this to her classmates, there was a certain sympathetic tone to her atrocities. There’s even a clear case of justification for her murderous escapade. She, however, has never been referred to as a serial killer in cinematic discourse but more as something closer to a misunderstood superhero. For trans women in media, their perception and representation are completely different with grave consequences. Historically, when they have been shown in mainstream media, there is an association of fear, intense violence against women, and an issue of severe psychological trauma on part of the trans character. Cis white women from Carrie to Cassie are given the guise of innocence and retaliation while trans women are stereotyped into monstrous creatures more often than not.

After being attacked and raped twice in one day, a timid, mute seamstress goes insane, takes to the streets of New York City after dark, and randomly shoots men with a .45 caliber pistol.

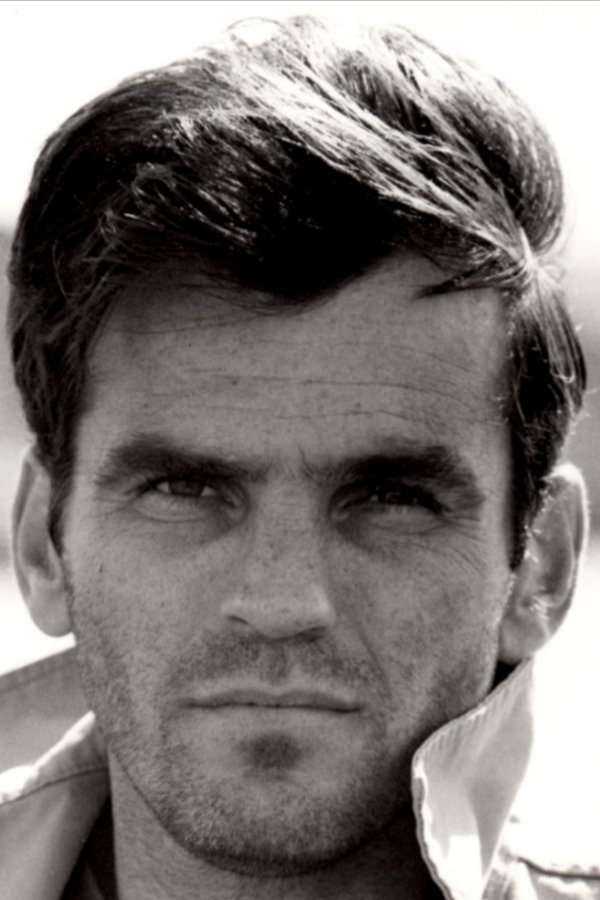

Abel Ferrara

Director

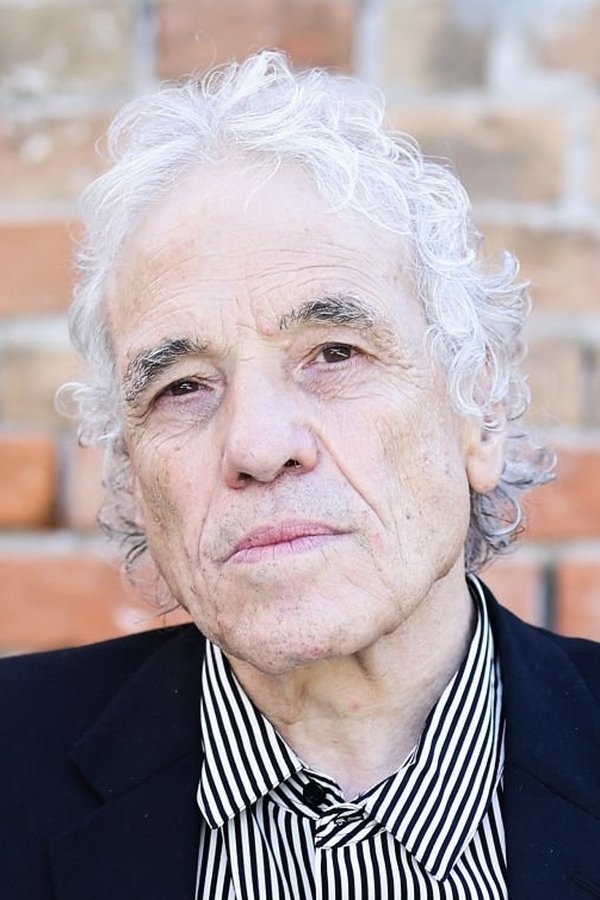

Abel Ferrara

Director

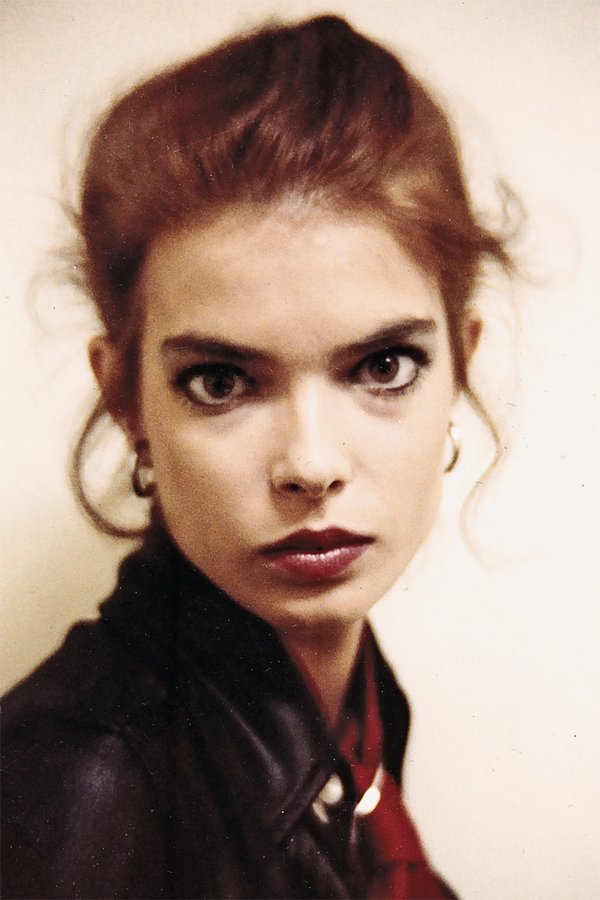

Zoë Lund

Thana

Albert Sinkys

Albert

Darlene Stuto

Laurie

Abel Ferrara

1st Rapist

Helen McGara

Carol

Editta Sherman

Mrs. Nasone

Stephen Singer

Photographer

Jayne Kennedy

Seamstress

Jack Thibeau

Man in Bar

Nike Zachmanoglou

Pamela

Bogey

Phil

Miles Morales learns to be his own hero as he takes on the well loved mantle of Spider-Man in a multiverse of Spider-People.

The Mandolorian has a more nuanced and commentative take on masculinity that refrains from praising the toxic traits associated with the social category, while also showing a more positive and transformative representation of masculine characters.

In Tall Girl, Jodi learns to stand tall and find confidence within.