Incluvie – Better diversity in movies.

Identity in film through scores, reviews, and insights.

Incluvie – Better diversity in movies.

Explore identity in film through scores, reviews, and insights.

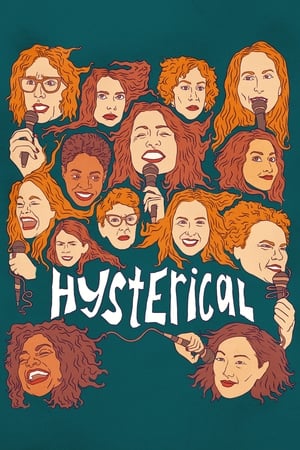

Hysterical (2021)

Incluvie Related Articles

'Hysterical' is an Absolute Must-See of 2021

April 28, 2021In recent weeks, I’ve been on a quest to delve into the disparities in representation within the stand-up comedy community. With no shortage of stand-up specials constantly being released across every platform, it seems only fitting to dig deeper into a behind-the-scenes look at how certain advantages and disadvantages take their toll on diverse joke-telling. Last week, my search brought me to Women Aren’t Funny, a documentary by comedians Bonnie McFarlane and her husband, Rich Vos. In my review, I noted that the mark was just slightly missed on the opportunity to disprove society’s theory on female comedians, as well as to inform on where that debilitating stereotype comes from.

My research on that film led me here: to Hysterical. An FX documentary currently streaming on Hulu. Discussing the same topic, Hysterical lends a much more modern feminist lens to the bias, as well as its subsequent consequences. Calling on the most notable women in comedy to offer their perspectives and personal experiences- I am delighted to say that this film hits all the right notes, and I could not be happier about it. So let’s dive in:

Every aspect of this film, technical and otherwise, is thoughtfully and carefully considered- accumulating to form an impactful piece on how women, including queer women and women of colour, are disproportionately affected by bias in the world of stand-up comedy. Representation is top of mind as the doc opens, citing how important it is for diverse voices to be heard- Margaret Cho admits that she never considered stardom as an option for herself because she had never seen Asian or female stars on comedy stages. Similarly, Marina Franklin attests her confidence as an up-and-coming black comedienne to watching Wanda Sykes rise to the top of her field.

The documentary poignantly addresses sexism in comedy at every turn, never failing to hit the nail right on the head. This is accomplished by way of interviews with the boisterous, astute and intelligent women of comedy. A huge takeaway for me was the acknowledgement amongst these women that men are not miraculously born with superior humour genetics. The stigma of men being the funnier sex has little to do with god-given talent, and more to do with the fact that men have always had the opportunity for their voices to be heard first. Men’s long-standing reputation in comedy doesn’t make them funnier by nature, just more advantageous. As obvious as that may seem, the effects of this unfair predisposition is still being felt to this day. The interviewees discuss how even the way a female act is introduced to the stage will affect the audience’s perception of their performance- or how one bad set from a female comedian at a club will make it nearly impossible for future women to get work months, if not years later. I appreciate the unique angles that this film fearlessly pursues. It is all made possible by the dedication of the comediennes interviewed and their commitment to this important discussion.

I Wish ‘Women Aren’t Funny’ was More Funny

April 20, 2021Here at the Incluvie newsrooms, we dedicate ourselves to the call to action surrounding diversity in film and T.V. While continuously adopting that critical lens as I watch both, I notice that I consider another favourite media-pastime of mine, stand up comedy, as a free pass: I don’t need to wear my Incluvie hat as I watch my favourite comedians traipse about the stage-- because it would probably spontaneously combust. In doing so, I never give myself the opportunity to challenge all the biases that go hand in-hand with the comedy genre; one of them being that female comedians are just less funny than men. My shift in attitude led me to the 2013 documentary Women Aren’t Funny, written and hosted by comedienne Bonnie McFarlane (and her husband, Rich Vos).

Female and racially diverse comedians suffer in numbers because of the ingrained belief that they’re less funny in nature, or that their humour is too specific- somehow less universally relatable. This documentary explores that bias from the perspective of fellow industry heavy-hitters (both male and female), as well as from various club owners- those typically in the position of giving fresh comedians their start in the industry. This film aims to be equally entertaining and humorous as it is informative, and as a result, it is unfortunately neither. There are chuckles hidden in the nuances of the writing and interview responses, but the comedic bits themselves seem over-extended. This is especially true right at the height of the film, when the findings of McFarlane’s thesis should take priority. Women Aren’t Funny calls itself a documentary but struggles to stay true to its style. The in-depth exploration of comedy becomes such a vast mix of different mediums that none of them are accomplished fully and effectively. The hard lean-in to the mockumentary form becomes frustrating when exposition begins leading up to an accumulative statistic or fact- only to deter from that final point with a poorly-considered graphic or gimmick that had me questioning the validity of the information, and similarly the strength of any given joke.

The bulk of the information we receive as an audience is captured in the form of interviews with comedians such as Sarah Silverman, Maria Bamford and Todd Glass. I observe that when female comedians are asked about the subject of bias within their careers, McFarlane is met with thought-out and witty responses. The male interviewees on the other hand are often dismissive, disrespectful or downright incoherent. Whether this speaks more to the character of her subjects than the host herself becomes increasingly clear as the film progresses. This subtly indicates that the root of the problem lives and dies with the front-runners of the industry as they do very little to change, or even acknowledge, unfair representations that they in turn largely benefit from. Though this may be a big ask from people who form an entire career from making light of a situation, I wish the interviews of Women Aren’t Funny were more direct and responsive so as to get a better grasp of the genuine perception of gender bias within the community.

Pictures and Videos

Movie Information

An honest and hilarious backstage pass into the lives of some of stand-up comedy’s most boundary-breaking women, exploring the hard-fought journey to become the voices of their generation and their gender.

Cast

Andrea Nevins

Director

Andrea Nevins

Director

Nikki Glaser

Self

Judy Gold

Self

Carmen Lynch

Self

Kathy Griffin

Self

Bonnie McFarlane

Self

Rachel Feinstein

Self

Margaret Cho

Self

Fortune Feimster

Self

Iliza Shlesinger

Self

Lisa Lampanelli

Self

Marina Franklin

Self

Articles You May Like

Trans Allegories in Film: 'The Little Mermaid' (1989)

Films can alleviate alienation by presenting realities where the viewers feelings are shared by onscreen characters. 'The Little Mermaid" film can be interpreted as a transgender story.

The First Asian-American on US Currency: Who's Anna May Wong?

Anna May Wong was a talented actress and a fashion icon and still had to fight for everything she had due to hatred and racism.