Incluvie Classics: Strong Women and Gender Expression in Alfred Hitchcock's “Psycho.”

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film "Pyscho" is an American film classic that still resonates today.

However, I heard the very same sentiment reverberated in The Sopranos itself with S4 Ep3, “Christopher,” an episode that focuses on Italian-Americans and their relationship to Christopher Columbus. And to me, this episode perfectly articulates an identity crisis unique to the Italian-Americans. It also demonstrates how the issues in Indigenous communities are pushed aside in favor of the ‘which culture had it worse’ debate.

At the beginning of “Christopher,” the news of a protest against Columbus Day appalls our central characters of this episode: Silvio and Richie. As many Italian-Americans do, they are under the impression that there is this conspiracy to defame Columbus, by the ‘commies’ and ‘Indians’ “that want to paint Columbus as a slave trader instead of an explorer” as Richie states, and by proxy, it becomes, as Silvio puts it, “anti-Italian-American discrimination” that “Columbus day is a day of Italian pride, it’s our holiday and they want to take it away.” To them, Columbus has become a symbol of Italian greatness, and they have ascribed him to hero status, even likening him to Martin Luther King, Jr.

Why do Italian-Americans want to claim Columbus as an example of a good Italian? Sure, he’s credited with the discovery of America, and that type of accolade definitely makes great PR for the Italian Community. Unless of course, we consider smallpox, slavery, and the fact that Columbus was sent back to Europe in shame for what we would now call crimes against humanity. But the reputation seems more important than the truth.

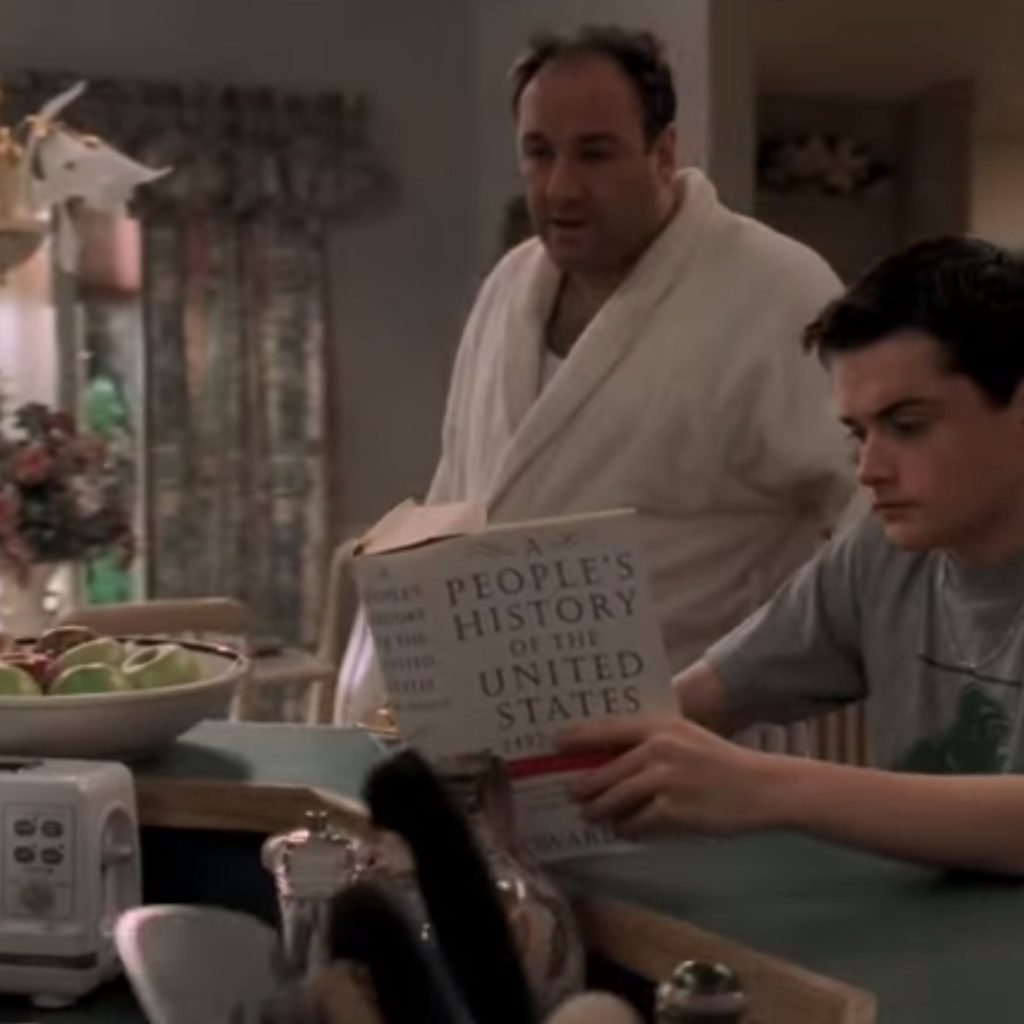

Many of the characters in this episode of The Sopranos unabashedly deny the allegations against Columbus, despite historical evidence of the contrary. In one scene AJ, Tony Soprano’s son, reads an excerpt from A People’s History of the United States. He reads the quote, “They would make fine servants, with 50 men. We could subjugate them and make them do whatever we want.” AJ adds, “That doesn’t sound like a slave trader to you?” And Tony who previously didn’t have strong convictions about Columbus suddenly feels inclined to save Columbus’s reputation as a fellow Italian. He impulsively shouts at AJ that “he discovered America, that’s what he did. He was a brave Italian explorer and in this house, Christopher Columbus was a hero. End of story.” Tony almost speaks of Columbus as if he is a personal relative of his, and defends him in the same manner in which he would have defended his mother or father in the earlier episodes.

The familial struggle seems to motivate the cries of Italian-American discrimination. The president of the Anti-Italian-American Defamation League- who speaks in conversation with Del Redclay from Carmela’s kitchen TV in one scene- tries to bring up an anecdote about his grandparents: “Two good people from Sicily who braved the middle passage…” In this one sentence, he is trying to lump in his grandparents’ immigration experience with the experience of African slaves. The moderator, a Black man named Montel calls out this comparison and the only rebuttal he has is, “Italian people also suffered.” Notice the past tense here. It slyly demonstrates the lack of contemporary suffering, only recalled suffering. In this scene too, Redclay advocates that a Parade for Columbus is deeply offensive for his people — but that is swept to the side once the middle passage is brought up and the conversation becomes ‘who had it worse’ not who is currently experiencing discrimination. Even on a so-called intellectual stage, again a ‘discrimination contest’ dominates the discourse intended to discuss the plight of Indigenous peoples.

Near the end of the episode Silvio recalls, “my grandparents got spit on because they were from Calabria” and Tony, now fed up that Silvio’s Columbus cause is costing him money, asks Silvio, “All the good things you got in your life, did they come to you because you’re Calabrese?… The answer is no. You got a smart kid at Lackawanna College…You own one of the most profitable topless bars in North Jersey. Now did you get all that shit because you’re Italian? No. You got that shit because you’re smart…” This goes over his head completely, he goes right back into the spiel that Italians suffered in this country. Notice the past tense again: suffered.

For Silvio, and many Italian-Americans, it’s the memory of discrimination that still resonates, not what happened specifically to them. From the stories they hear from their parents or grandparents, they feel obligated to defend Columbus because he too, symbolically has become a part of the ‘great Italian family’.

A lot of Italian-Americans believe they are under discrimination, which is not completely unfounded. As the result of economic hardships, and later, the rise of fascism in Italy, many Italian citizens (mostly southern Italians) fled to America in droves. Italians, like many immigrants after them, would take lower-paying jobs and often were financially exploited as agriculturists and laborers. Naturally, mass immigration of any population that differs from White Protestant Anglo-Saxons terrifies many Americans. Many feared a mass foreign population would be hard to assimilate, others feared Italians would bring socialist or anarchist political views due to fascism in Italy. And, equally many Americans had pre-existing animosity towards Catholics inherited from the Protestant/Catholic conflicts of Europe. It is true that many Italians were wrongly imprisoned (think of the Sacco and Vanzetti case), and the largest known mass lynching in America was of eleven Italians in Louisiana.

In those early days, Italians were treated how America treats many of our immigrants today: Americans feared encroachment on the American job market, they feared their customs, their religion, their politics, etc. But that same discrimination has little to do with the present day, nor the day of the Soprano Mafia. But many Italian-Americans feel it still exists because they romanticize their ancestors’ struggles in America.

By the end of the episode, Tony has changed his perspective on the whole Columbus debate. He advocates for a bit more individualism and urges his friends to stop portraying themselves as victims of discrimination, not exactly because it’s wrong but because he considered it embarrassing. When Silvio says, “Hey people suffered,” Tony pointedly responds, “Did you?” Tony prescribes the Columbus adoration as a self-esteem problem. And perhaps he’s right. Italian-American pride doesn’t come from “Columbus or The Godfather or Chef f—kng Boyardee,” and they should not rely on cultural figures to give Italians a good name, but instead, earn that reputation on a personal level. Wise advice I think even my grandfather would agree with… even coming from a fictional Mafia boss.

(This article was originally posted by Isa Maginnis on Medium.)

Related lists created by the same author

Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film "Pyscho" is an American film classic that still resonates today.

Related Movie / TV / List / Topic

The cancelling of these series is being blamed on the writers' strike and low viewership, but it's just the latest example of the industry's lack of appreciation for stories about queer women.