All Hail The Queen of Basketball, May She Reign in Peace...and Win An Oscar

In less than 30 minutes, Proudfoot guides the viewer through a narrative that touches on American history, mind-health issues, race, and gender politics

Patrick Somerville’s Station Eleven made me think about my grandma Alice, a quilter born in 1908. Like Miranda Carroll (Danielle Deadwyler), she was an artist but would’ve never fashioned herself such. A cartographer of sorts, my grandma likely picked up this tradition from the Black women she descended from, women traced back to Cameroon. It is believed that quilts held codes to assist enslaved Black/African people in navigating freedom. These messages, hidden in plain view, stitched hexagons, squares, triangles into designs like: “bear paw,” meaning take a path out of sight, “log cabin” indicating it was a safe haven, or “drunkard’s path” (one of the last designs my grandma quilted before she died), signaling the need to zigzag along a path to avoid detection. Once maps for the Underground Railroad, some quilts are now artwork on display in homes and museums. Other quilts, worn to pieces, are a repository of their owner’s DNA, blood, sweat, and tears from the many nights used to wrap around in comfort.

You might ask: what in the world does this have to do with Station Eleven and the graphic novel’s name central to the story? Though the writer likely did not intend, I discovered subtext based on my worldview. For example, Lori Petty’s character is named Sarah, also known as “The Conductor,” the co-leader and composer of The Traveling Symphony. Sarah influenced who joined the group and which direction they might move; similarly, “conductors” along the Underground Railroad guided safe passage. More specifically, like a quilt, the series stitches characters together in coded patterns revealed along the way to the final episode. Station Eleven was a symbolic work of art; its eponymous graphic novel at its core—a map, a comfort, a memory holding coded messages—like the patterned language of characters themselves.

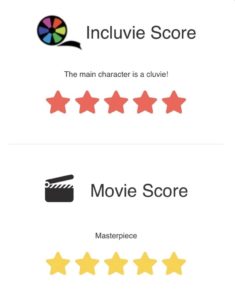

The unwitting artist and cartographer in Station Eleven, Miranda was a complex Black woman with a Byzantine mind played with a flash of subtle brilliance by Deadwyler. Her character is the centroid to the triangulated themes in the series I reference later. That it was, in fact, a Black woman responsible for creating the “North Star” (the graphic novel) of the series was a meaningful casting decision by Somerville for me. This is partly why it rates high on my Incluvie scale and grounds me as a spectator inside this speculative narrative.

A post-apocalyptic tale about what happens after a flu pandemic, Station Eleven premiered amid our worldwide coronavirus outbreak. For many, watching this series could be filed under “too soon;” admittedly, there were moments I almost hyperventilated watching it myself. But there seemed to be a prescient connective tissue between the road we were on and that of the imaginary road “The Traveling Symphony” traversed to St. Deborah by the Water and back again. And, despite my pandemic PTSD, this series was a storm and the calm within it. There were many small moments where I was literally moved to tears.

Mackenzie Davis and Matilda Lawler were both equal forces playing the older and younger versions of Kirsten Raymonde. It was a marvel watching each of them embody the other’s age and maturity. In one scene, Davis lies in the grass reading Station Eleven. Her body positioned like a child might, quite possibly the age her maturity halted due to the trauma she experienced. And then younger Kirsten wields a blade and gun to kill for food or protection, like an adult might. But even with Kirsten’s significant screen time and storyline, Station Eleven appeared to be intentionally inclusive. Each episode featured a diverse cast of characters, including Miranda, Jeevan Chaudhary (Himesh Patel), Frank Chaudhary (Nabhaan Rizwan), Miles (Milton Barnes), and Arthur Leander (Gael Garcia Bernal). Most of the ensemble cast held consequential roles. Survival was also possible in part because of characters like August (Prince Amponsah), Wendy (Deborah Cox), Chrysanthemum (Ajahnis Charley), to name just a few.

As referenced above, I found three major themes that became my lessons from Station Eleven that absolutely matched what I learned during the pandemic. In part, this is why I would suggest that once it’s not “too soon” for you to watch it.

Love. Love can be painful, devastating, gut-wrenching, and worth every moment wrapped inside it with your beloved (albeit lover, family member, faithful friend, or fellow survivor). When all else dies, and it will, what survives and even thrives is love. And at the core of Station Eleven were two love stories: one between Kirsten and Jeevan, who became each other’s immediate “chosen family” or maybe more accurately described, “fated family.” And then, they expanded with Jeevan’s brother, who grew into Kirsten’s beloved brother as they formed their pandemic pod. They all suffered through the tremendous loss of family, loved ones, and familiarity, shifting and regrouping into who they needed to be to survive. Frank ultimately understands his sacrificial role as a motivational leader. In one fantastic scene, to help them manage their first Chicago winter, he makeshifts into a beatbox then performs A Tribe Call Quest’s “Excursions” —a moment of unadulterated joy… love.

Then the story between Miranda and Arthur, hopeful, then not, but true lovers whose depth of emotion, for me, was found in the quiet between them as they fell in love. There were also monumental yet simple exchanges as they fell apart and found each other again, even late. When Arthur laments to Miranda, understanding he’s lost her to her art, “Even when you are here, you are not here.” Then years in the future, after their divorce, Arthur’s remarriage, and then dissolution, they meet again. She finds him having completed the book, gives it to him, and promises to return after her ill-fated trip to Malaysia. While desperately trying to get back to him, she learns he died on stage playing King Lear just the night before. And in an awkward and scary moment of awakening at her logistics business meeting, she says, “The man I love died last night, and I went to work instead.” This simple line, for me, put in context an overarching message, the significance of love.

Regret. The pandemic provided time for people like me who ruminate to ruminate more than ever over 1) people I wish I’d spent more time with, 2) things I have not accomplished, or even in the “post-apocalypse” 3) I really wish I’d work out more than I drank wine, etc. But also, to not let myself get mired down in the quagmire of regret. Who has the time? And there were some specific moments and quotes in Station Eleven that summed up the feeling of regret:

Art. Like oxygen, you take it for granted and don’t often think of it, but you can feel it when deprived of it. And what I mean by art is relative to the human. It is the “strange and awful time” that Frank refers to as “the happiest of [his] life.” It is also the “sweetness on earth,” Miranda references she tries to remember while “overlooking the damage,” as well as “calamity” and “escape.” The Traveling Symphony’s performances, music, dance, Shakespeare, and Miranda’s graphic novel—her art—were all as necessary as the air they breathed. In our non-TV world, we found ways to thrive as artists or aesthetes, even if fledgling. We sought out dancers who performed via FB live, artists who shared their portraits on TikTok, or chefs whose beautiful meals were concocted on IG. We saw theatrical plays where actors were in their pods with Zoom as a stage. We listened to poets and musicians from around the world collaborate on lyrics and verse, who might not have ever performed together had it not been for the pandemic. We craved film—in all its genres and forms.

So, in getting back to my earlier point, like my grandmother, Miranda was a quilter piecing together lives and connecting them into her own piece of art, Station Eleven. And in this case, life not only imitated art, but art imitated our pandemic lives—in all, its raw and ferocious beauty.

Related lists created by the same author

In less than 30 minutes, Proudfoot guides the viewer through a narrative that touches on American history, mind-health issues, race, and gender politics

Related diversity category

'Jungle Cruise' is fun if you can ignore the racism of the ride it’s based on and the film’s bland, stereotypical characters.

Related Movie / TV / List / Topic

This Halloween movie is a remake of the 2003 movie of the same name with Black representation.