Spider-Man: Across the Closet with Miles Morales and Gwen Stacy

The film's storylines read as allegories for the queer experience and that's a source of solace for LGBTQIA+ fans!

During the weeklong Kolkata International Film Festival, the complex of Nandan in Kolkata, India, is filled to the brim with cinema fans. From film enthusiasts, art students, media representatives, critics, and retired people, Nandan is swarming with people interested in cinema. The movies range from the most obscure Belgian queer film to the most famous film of the local heartthrob. The queue to get tickets for any show is significantly long and many people have to be turned away because seats fill up that quickly. 20th December was no exception, and Nandan’s main hall, one of the largest movie theaters in the city, was filled to the brim, with people standing or sitting on the staircase even!

It was 4:30 PM and the film being screened was the first ever Pakistani Cannes Film Festival entry, filmmaker Saim Sadiq’s directorial debut, Joyland. No matter what their individual opinions about the country and its people, the audience as a whole fell silent and watched in wonder as a tender, heartfelt, and compassionate narrative about the tragic impact of patriarchy on the lives of unsuspecting and innocent ordinary people unfolded on the screen over a span of two hours. The standing ovation at the end was inevitable, but a mournful and contemplative silence had fallen over the audience. Was the ending cathartic? People were trying to make up their minds.

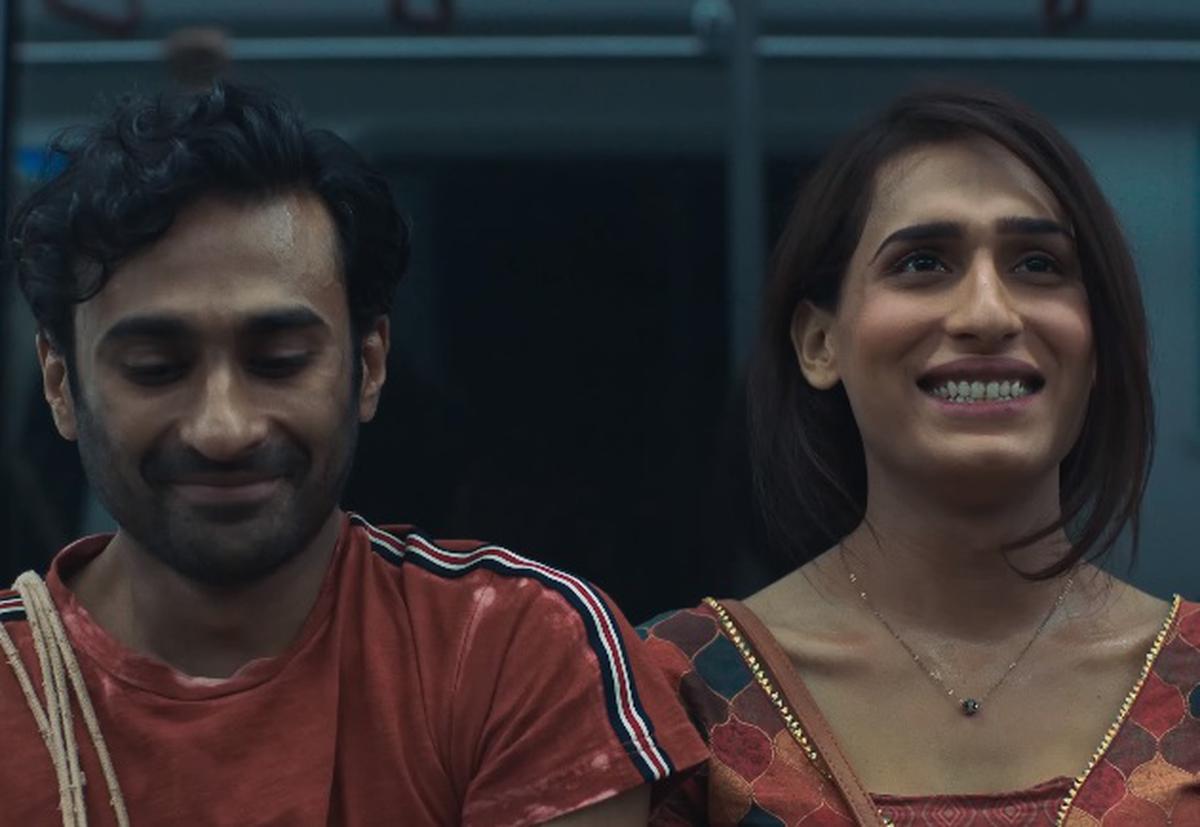

Joyland has been making waves in media circles ever since it was screened at the Cannes Film Festival and won the Queer Palme. It’s the first film from Pakistan to win at Cannes, and was shortlisted for the Oscars. It tells the story of the Rana family and how its members are affected by patriarchy and cisheteronormativity. The patriarch of the family, Amanullah (Salmaan Peerzada) is waiting for the birth of his first grandson. His elder son, Saleem (Sohail Sameer), is married to Nucchi (Sarwat Gilani), who has had three daughters with him and is pregnant at the start of the film. The younger son, Haider (Ali Junejo), is jobless and stays at home with Nucchi, helping with household chores and looking after his three nieces, while his wife, Mumtaz (Rasti Farooq), works at a beauty parlor doing makeup for rich clients and earning significantly. Amanullah doesn’t like the fact that Haider plays the role of a homemaker while Mumtaz is the earning member in their marriage. He doesn’t say anything explicitly, but his body language makes it clear that he believes that Haider has been emasculated. Things change when Haider gets a job as a background dancer to transgender performer Biba (Alina Khan). However, fearful of the toxic masculinity of his father, he tells the family that he is a theater manager.

The family tells Mumtaz to stop working because Haider has a job. They insists that Nucchi will have to be alone at home with the kids since Haider will be going out for work now. Mumtaz and Haider both stand up for her independence, but are silenced by the latter’s father and brother. Working with Biba is a liberating experience for Haider and he stays back with her late at night every day. Mumtaz stays at home with her sister-in-law and father-in-law, missing her job and her husband. Her mental health begins to deteriorate and their marriage becomes strained as a result. Meanwhile, tensions rise within the family because it’s revealed to them that the theater Haider manages hosts a transgender dancer. Haider spends even less time at home, but Mumtaz has something to be thankful for, as Nucchi takes initiative and bonds with her. They spend time with each other, sometimes frolicking and sometimes finding solace in confiding the struggles that the patriarchal family puts them through. Joyland takes its time exploring the various interpersonal dynamics between its characters, and instead of pointing fingers at characters who’ve been brought up to not know better, it makes a primary enemy out of the cisheteronormative patriarchal society we live in.

Even the character of Amanullah, the problematic head of the family, isn’t vilified directly by the narrative. Instead, the story treats him sympathetically: viewers are invited to feel sorry that he has been conditioned to uphold these archaic and oppressive rules which harm him too. He is close friends with Fayyaz (Sania Saeed), a widow who lives next door, but their relationship is not balanced. While she dedicatedly dotes on him, he gives her bare minimum attention because of his concern about taboos and what the neighbours will say. Through this dynamic, the film depicts why he may be at wrong for treating Mumtaz the way he does, but also that he isn’t the original culprit. It’s the societal norms which are largely at fault.

Saleem’s character arc moves in a similar direction. He loves his brother and cares about what happens to him and his marriage, but his toxic masculinity prevents him from displaying affection in a healthy way. Instead, he bullies his brother out of ‘concern’, and this effectively strains his relationship with Haider. Instead of crucifying men, Joyland, while not shying away from depicting their misdeeds, makes the nuance point that they’re victims of the patriarchy as well.

While Joyland is brutally honest in its depiction of Haider’s ostracization in the family because of his effeminate body language, his habit of not dictating what his wife can and cannot do, and his close association with a transgender woman, it doesn’t treat him like a martyr. Sadiq handles queer trauma with utmost care, ensuring he doesn’t tokenize the queer characters or become self-indulgent in their suffering, while showing the World how queers are treated in his homeland. Biba has a fierce personality and she stands up against all kinds of shaming, which doesn’t just come from outsiders, but also from her own troupe, which consists mainly of men, who are misogynist and internally transphobic to various degrees. And yet, she has her own moments of weakness, especially with Haider, when his own willingness to explore sexuality makes her cringe. Instead of making her saintly or stereotypical, Sadiq humanizes her through her flaws. The same is true for Nucchi and Mumtaz. Nucchi’s bond with Mumtaz is born of a sisterly concern on the former’s side, but she is complicit in the patriarchal mistreatment of Mumtaz. All the characters are layered, and this gives them a sense of authenticity, while adding to the lived-in feel of the world that Joyland is set in.

Haider goes through a queer awakening. The liberation from toxic masculinity and family pressure almost immediately makes him more physically expressive than before. He couldn’t dance well, but it doesn’t take him long to become good at it. Haider’s effeminate nature is depicted in the very first scene where he is seen playing hide and seek with Nucchi’s three daughters. Amanullah wants him to kill the goat that is to be prepared for their meal because the butcher isn’t available. Haider’s father brutally emasculates him with his words because he isn’t able to get the job done. So Biba represents the ultimate independent soul to Haider, and working with her presents an opportunity for him to finally adopt the body language he yearns to express himself through. But his transformation goes beyond this. His behaviour insinuates that he’s questioning the identity that his family associates with him. Sadiq’s sensitive treatment of the subject matter is beautifully composed. He doesn’t depict Haider going through the more Western customs of crossdressing to question one’s identity or hanging out in gay clubs to experiment sexually. Instead, it’s in the little things about Haider’s behavioral patterns that his queer-questioning comes through. The way he talks or walks or simply the way he looks at Biba, and perceives the concept of gender – the possibility of him going through a queer awakening is subtly but firmly planted into the viewer’s mind. The lack of labels about Haider’s sexual identity is liberating because he’s just begun a journey and is going through changes.

On the other side, no one respectfully calls Biba a woman or a transgender woman. This is a commentary and indictment on the awareness in Pakistan and its neighbouring countries. In the film, the stigma is portrayed by women on the metro who don’t want Biba sitting beside them, the theater manager who doesn’t want to display Biba’s poster out front, and the negative reaction from Haider’s family. Haider himself just tells his wife that Biba isn’t a woman in the strictest sense, and Mumtaz pays this forward by introducing Biba to someone else as the woman who is of ‘that’ kind. That is the most respectful way she is addressed in fact. I know fluidity can be liberating when it isn’t accompanied by labels, but Biba’s identity is never healthily acknowledged, and her mislabeling and misgendering is oppressive.

It feels very old Hollywood and reductive to define a hero and a villain in a film like Joyland, but the fact that it presents the patriarchy as this overarching antagonistic presence is commendable. Amanullah and Saleem are both disappointed that Nucchi gives birth to another daughter. Neither of them are good to Haider, and their “support” comes in the form of bullying in the name of “tough love.” They’re victims themselves because their patriarchal worldviews restricts their own self-expression. Amanullah genuinely cares about his children, their wives, and also his friend Fayyaz, but he’s unable to convey that to any of them. He’s afraid of appearing weak if he shows emotion.

It’s the same with Saleem, as he is poor at communicating with his own wife. She speaks somewhat openly with him, but his responses are emotionally distant, often incoherent because he isn’t paying full attention. These are very common scenes in South East Asian households, but it’s not often that this invisible culprit is acknowledged. The World often makes the patriarchal figures the sole enemy, and they often respond with worse or more violent actions, which only worsens the rift. Beyond holding them accountable, it’s necessary to realize that this is the effect of patriarchal social conditioning, and that the problematic men are themselves victims of it, primarily in the form of toxic masculinity. This can take us out of a reactionary cycle, and begin to cut at the roots of this ancient problem.

Joyland also explores patriarchal conditioning in the form of internalized misogyny in women. And instead of making a spectacle of this, Sadiq presents an authentic picture of how this happens. Nucchi isn’t shown to be jealous of Mumtaz for having a job and being “allowed” to earn. Instead, when the latter loses her job and they start spending more time together, Nucchi confides in Mumtaz that she also had aspirations of working. She consoles Mumtaz by saying that they cannot work because that’s the way it’s supposed to be – the men will earn and the women will be homemakers. It’s clear she feels sad on Mumtaz’s behalf as well, but the notions prevalent in the society have made her think this way as well. To the Western World or more aware places, this might seem like an unnecessary point to make, but being a citizen of India, I can vouch for the fact that this also constitutes nuance here, and even these conversations still need to be had.

The transphobia that Biba is subjected to is juxtaposed against her own mistreatment of Haider when the latter tries to be the bottom in their sexual activities. This is the result of cisheteronormativity, itself is a patriarchal construct. The lack of understanding and compassion is what births the definition of ‘normal’ and causes the queer shaming which most LGBTQIA+ people face. By showing that Biba herself isn’t completely open-minded, Sadiq has made the important point that it’s the social norms which cause this, as the lack of education makes her close-minded outside of the queerness she has experienced herself. This indirectly shows the limits of our own experiences, and the need to listen to others to broaden our world.

The depiction of toxic masculinity is also kind of unique in Joyland. It’s not just portrayed through dialogue or character writing but through the visuals themselves. The picture of a man standing over a goat with a knife in his hand is often visualized as a display of strength. Instead, in Joyland, that scene is framed in such a way that the man himself is seen as the victim. The low camera angle, the focus on Haider’s eyes which are betraying fear, and the exclusion of the goat from the close-up shot, convey the discomfort in the protagonist, instead of making him look powerful. The participation of the visual aspect is best felt in the now-iconic shot of Haider riding a bike with a poster of Biba. The poster looms large against the night sky and she looks confidently defiant, unaffected by all the looks from passersby. Haider himself is completely oblivious of others’ reactions, and is just focused on storing the poster properly to ensure it doesn’t get damaged. His dedication to Biba is the focus in this case.

This section contains major spoilers, so skip ahead to the conclusion if you haven’t seen Joyland yet.

Although the film treats all its characters with care, giving them enough time to be fleshed out, I could never have predicted the ending which focuses on Mumtaz, despite Haider and Biba seeming to be the central characters. Mumtaz’s suicide feels like the perfect direction for the third act, though. If Joyland is a critique of patriarchy, then commentary on how her family members’ toxic masculinity and misogyny slowly caused Mumtaz’s mental health deterioration is essential. Becoming pregnant with a son pushes her to take the extreme step because her husband is absent, and her immediate surrounding family is ready to make her life all about her unborn son, while her dreams of going back to work die. But it’s not that simple, and the deterioration is very slowly shown through the runtime of Joyland. The flashback to her meeting with Haider before wedding also shows just how much he adored her and doted on her. It’s tragic that his queer awakening came at the cost of his affection for her. Their love is a victim of patriarchy, because she gets trapped at home, which he tries to escape from, and as a result their relationship suffers.

Related lists created by the same author

The film's storylines read as allegories for the queer experience and that's a source of solace for LGBTQIA+ fans!

Related diversity category

Kill Bill: Volume 1 is a highly entertaining flick, designed to tap into our levels of adrenaline. Tarantino has crafted a cinematic winner, overflowing with nostalgic richness and a love for cinema.

Related Movie / TV / List / Topic

This 2016 winner of an Ophir Award for Best Film focuses on the forbidden romance of a young, Bedouin woman and the ramifications it has for her family, her identity, and her culture.